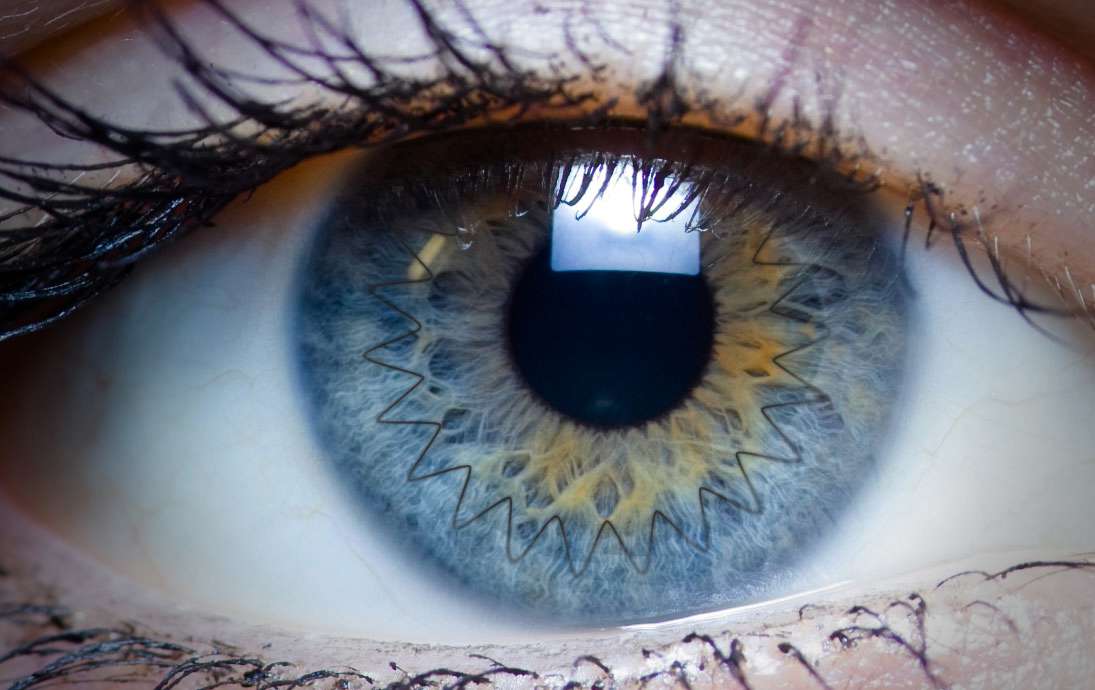

Twenty-nine years ago, a miracle happened. But first, allow me to back up to the very beginning. At fourteen months of age, I was diagnosed with Scheie Syndrome. Google it if you must, but I’m warning you - some of the pictures are unsettling. You see, Scheie Syndrome is a less-severe version of something called Hurler’s Disease. Now that one’s real scary – misshapen features, physical and intellectual disabilities, and an average lifespan of ten years. Scheie Syndrome’s primary symptoms are cloudy corneas and decreasing vision. It’s akin to looking through a very dirty window. Eyeglasses don’t help. That, my parents were told, would be like covering that dirty window with another one. Corneal transplants were in their infancy during the 1960’s, and Dr. Harold Scheie, my ophthalmologist and the person responsible for identifying Scheie Syndrome, warned my parents to avoid transplants at all cost. The new corneas would cloud up, too, he said. So you live with it. I didn’t know my vision was different from anyone else’s until my first day of school. Our teacher wrote the letters of the alphabet on the blackboard and had us copy them. I couldn’t see the board. That wonderful teacher, Mrs. Hurlock, knew this already. “Move closer so you can see,” I remember her saying. ‘Closer’ was four feet from the board. That became my spot. I’ll save the details for a future post, but my vision remained steady through my mid-twenties. Having never experienced good vision, I couldn’t fully appreciate what I was missing. I’d always held books two inches from my nose and struggled to recognize friends from further than ten feet. Like many kids, I graduated, went off to college, and got a job. I’d been teaching for five years when I noticed my vision was dimming. Teaching notes had to be larger. Lighting had to be brighter. After avoiding the eye doctor for years, it was time to return. For the better part of an hour, a staff ophthalmologist at St. Louis University Hospital examined me with scopes and bright lights. After one last check, he jotted a few notes, and turned to me. “You need a cornea transplant.” Remembering what my parents were told a quarter-century earlier, my response was quick: “I want to see your boss.” I learned two things that day. First, some doctors don’t appreciate being second-guessed. Second, medical technology had come a long way. The head of the SLU Department of Ophthalmology was a kind man named Dr. David Schanzlin. He ooohed and ahhhed when I told him of my childhood visits with Dr. Scheie. “A pioneer,” he said. “His work shaped our field… but times have changed.” Then, he threw out the line that clinched it. “You’re going blind.” With little to lose, I had my name added to the list for a donor cornea. In 1987, the wait could be anywhere from one to six months. Then, the second week of January, I received word that I was nearing the top of the list. “Stay near the phone and be ready to leave for the hospital,” they told me. The date was January 25, a Monday. I was in class when the office said I had a phone call. “Mr. Wootten, we have your cornea.” That was twenty-nine years ago this week. The transplant was so successful that the twelve-month waiting period between transplants was waived. In June, I received my second transplant. Two months later, I was fitted with contact lenses. A month after that, at age twenty-nine, I got my driver’s license. Forty days after that, my first speeding ticket. That transplant gave out three years ago, one year past the twenty-five year life expectancy of a cornea. I received a new one. It’s doing well. My left cornea will be twenty-nine this summer. It’s also doing fine, and says hello. I divide my life into two parts. There were the twenty-nine years before my first transplant, and this month marks twenty-nine years since. Both parts are chockful of blessings and challenges. I screwed up plenty of things before and after, and made a few good decisions, too. I sure do like seeing. How about you? Are you an organ and tissue donor? I’ve heard the reasons not to sign up: “I want my organs with me when I’m buried,” or “it creeps me out.” More to the point, I’ve experienced the good that comes from organ and tissue donation. If you’ve registered as a tissue donor, please let me know, either by email, on my Facebook page, or in the comments section below. If you want to sign up, go here or click on the picture of the eye, sign up, and let me know about it. I’ll pick one donor at random to receive a complimentary signed copy of my upcoming book, Shunned. And as always, thanks for reading.

15 Comments

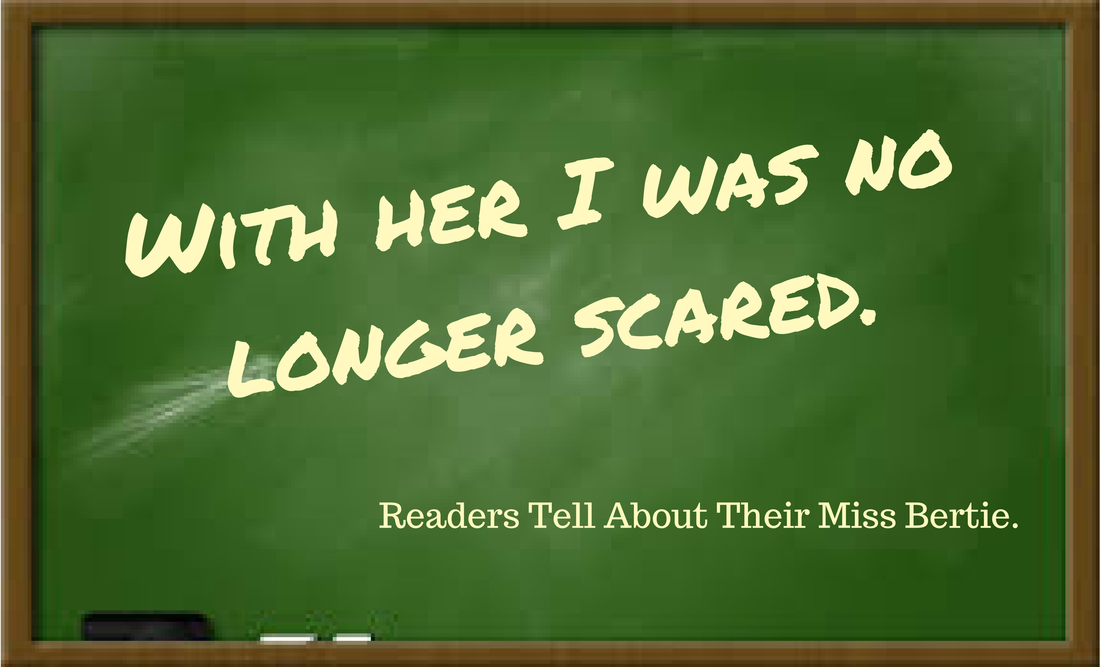

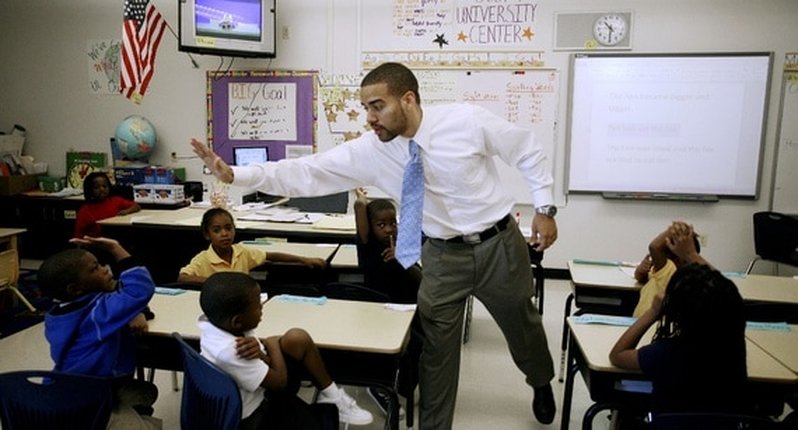

The statement above came from an adult, writing about the teacher who reached out to her as a thirteen-year-old during a most difficult time of her life. Wow! I asked about your Miss Bertie and you let me know. You responded in the comments section of this blog, by email, by Facebook Messenger, and by text. The Miss Bertie in your lives taught elementary and high school. Your Miss Bertie was an English teacher and a Wrestling Coach. She taught Home Economics, Math, Art, and Music. He impacted you in public and private schools. It turns out, Miss Bertie is everywhere. Here are a few excerpts: “I wanted to be just like him.” “She was creative and innovative.” “He taught Math in a way that was less about Math and more about who I was going to become as an adult.” “He brought out the good in me.” “She was instrumental in developing my ability to do presentations and speak in public.” “He loved his subject and cared about each and every student.” “He taught me it was okay to express an opinion that wasn’t necessarily the opinion of others.” “She made Chemistry and Science fun... without me really knowing how.” “There was no other teacher who made me believe I could go to college or become a teacher.” “He knew I needed encouraging, and he gave it.” “I became a stronger person with his direction.” “He made me want to be a teacher.” “Her influence on my life was profound.” “I miss her dearly.” If you haven’t shared about the teacher who was your Miss Bertie, please do. I’ll be picking one at random to receive a complimentary copy of Harvest of Thorns. You can respond in the comments section below, by email at [email protected], or on Facebook. I’ll be sharing more stories in a couple weeks. In the meantime, if you haven’t met Miss Bertie, you can find her here. Miss Bertie was his seventh-grade English teacher. Tough old nag, from what he’d heard. He knew from three weeks in class that she was demanding… she seemed bigger than everybody at school – Harvest of Thorns.  "Happy Birthday Miss Jones," by Norman Rockwell No character has generated more feedback than Miss Bertie - Chan’s teacher, mentor, and friend. When Miss Bertie saw how hard life was for Chan, she started looking out for him. We’ll never know everything she did for him, but we have a pretty good idea. How do we know? Because many of us had a Miss Bertie in our life. I’ve been asked if Miss Bertie was based on someone from my past. Was she one of my elementary or high school teachers? A colleague? Was Miss Bertie even a Miss? Could she have been a Mister? I’m not saying. Everyone has their own Miss Bertie, and I don’t want mine to be any more important than yours. A reader sent along an email about his Miss Bertie: Paul, my Miss Bertie was a lady named Mary Schean. 9th grade English. We had Ivanhoe and diction drill. I still remember a bunch of her words. Others describe their Miss Bertie as music teachers, coaches, and club sponsors. Regardless of what they teach, the Miss Berties of the world take time to really know their students. In most every case, it isn’t so much what they teach as how they teach it. Somehow, in the process of teaching, they also change lives.

So, here’s the big question – Who was your Miss Bertie? Respond in the comments section below, on my Facebook page, or send me an email at [email protected]. You don’t have to use your Miss Bertie’s real name if you prefer not to; just a few sentences about how they made a difference. I’ll pick one submission to receive a free copy of Harvest of Thorns. Back in the 1990's, someone asked my friend Larry Deaton how long it takes to transition to retirement. Larry responded, "Let's see... how long does it take to drive home?" In 2011 I turned in my keys and left behind thirty years of public education. I wasn't sure what I wanted to do, so for a few weeks I walked. And walked. For hours. Every day. Robin grew concerned. Our dog Chloe hid whenever I put on my walking shoes. That was my transition period. Longer than Larry's, but just right for me. Then, opportunity: Proctor and Gamble was looking for a merchandiser, someone to set displays, align shelves, and check inventory. Part-time, which was perfect, as I was wanting to try some writing. For five months, I visited stores and did what merchandisers do. It was enjoyable work, until P&G announced it was outsourcing its merchandising. At the same time, a help-wanted ad appeared in our local paper - Reporter Needed. I shot off an email and... was a day late. Still, the editor asked if I'd consider freelance feature writing. What a blast! I wrote articles about interesting locals like my friend Bill, a small-engine mechanic who jumps from airplanes and prepares award-winning barbeque that gets featured on the Food Network. Like merchandising, it was a great job until it wasn't. Within a few months, the Pointe was no more. Profitability can be elusive for small-town newspapers, and my second job came to an end. You're probably starting to see a pattern here. Paul gets hired, company runs into trouble. I had to disprove that theory, and the best way was to go to work for the Kansas City Royals. They were already in trouble. Twenty-seven years without a playoff appearance, players leaving left and right. I couldn't hurt them, right?  Fortunately, the Royals’ fortunes turned for the better. You can read my account of the Royals years here. In addition to being around great people, I got the chance to do a little writing for Royals' Baseball Insider, the in-stadium magazine. Human-interest stuff, mostly. No player interviews or anything like that. Still, it was writing. Along the way, I had this idea for a book. It started with Chan Manning. He'd been in my head for years, trying to find his way out. In 2012 I let him out. Unbeknownst to me, Chan had friends who came with him. Harvester Stanley, Miss Bertie, Theresa Traynor. The more I wrote about Chan, the more I wanted to know about him. Out came his father Earl and grandfather Levi. I basically wrote Harvest of Thorns in reverse, not something I recommend. There were plenty of fits and starts. I stopped writing Harvest for a few months in 2012, moving on to the manuscript that became Shunned, my next release. A book should never take four years to finish, but Harvest did. There probably isn't another Harvest of Thorns in me. 130,000 words in one book is too much. I hope my future books, mostly in the 70-80,000 range, continue to tell stories people want to read. The lessons have been many. I thought I knew how to write. Ha! There's still plenty to learn and I'm into my third book. Still, I wouldn't change a thing, even when my characters wake me up in the night, telling me what they're going to do next. Even when my thumb drive breaks in half and I have to pay $200 to retrieve my manuscript (Save to the cloud, folks!). Even when I attend a writer's conference and get shot down by publishers. And shot down again. And again. So here we are. It's January, 2017. Time for resolutions. Mine include publishing two more books and completing the manuscript for a third. I also plan to visit Europe for the first time. If you've been to Greece and Italy and have recommendations, send them. Oh yes, I want/need to lose the same fifteen pounds I resolved to lose in 2016. And 2015. And 2014. How about you? Resolutions? Schemes? Big ideas? Share 'em if you got 'em! Happy New Year! |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed