If you attend sporting events, be it major or minor league, you see them. Or maybe you don't. They check your ticket and, if you get too adventurous, they gently remind you that the seats you're sitting in aren't yours. For most of my life, I scarcely noticed them, other than to check where they were before sneaking down the aisle to better seats. Then I became one. An usher. My son Cody and I applied together. He wanted money for college. I liked the idea of a part-time retirement job that allowed me to watch baseball for free. Robin encouraged me. "You're going out there anyway," she said. "You might as well get paid for it." Cody and I were both hired. He worked the first base side. I worked the third, behind the visiting team dugout. After a couple years Cody moved on to bigger and better things. Five years later, I was still there, in the same spot I'd occupied throughout. Section 123. The Royals weren't very good the first couple years. Crowds were small and much of my time was spent chasing people out of the same seats I'd snuck into a few years before. There were games - lots of games - when fans from visiting teams outnumbered our own, including Yankee games when Bronx cheers drowned out Midwest twang. But then, the team started to get good. Real good. A World Series in 2014 ended with the tying run on third base in the bottom of the ninth. Then, in 2015 the Royals won it all! As you can see from the photo above, Kansas City loves a winner. That's the World Series parade held 13 months ago. The sea of blue is people. Hundreds of thousands of people. 2016 was my final year as a Royals usher. I want to write a little more and travel a little more; the time requirements cut into family get-togethers sometimes. Then there is the physical wear and tear from standing on concrete for hours every night. But man, am I glad I had the chance to be an usher. A week doesn't go by without someone asking what the job is like. So, I'm going to answer that question here, one last time, for everyone. It's one of the greatest gigs ever. I don't use the word, 'awesome' very much, but man did I work with some awesome people. Our usher crew was tight, and made coming to work fun. We were a melting pot really, with all backgrounds, lifestyles, and colors represented. None of that mattered. We were a team. But, you want to know something? Even better than the crew I worked with were the people who turned out for Royals games. Especially the regulars. My section was populated by season-ticket holders. Most had been showing up since the dark days. Celebrating playoff championships with them was an indescrible experience. Over time, we moved past being usher and fans. We became friends. One couple visited us in Florida. Others have become dining partners. We know the names of each others' family members. We graduated kids together, married off kids together, and became grandparents together. We mourned the losses of a few of our regulars, but celebrated our memories of them. I'm gone from the park, but these friends stay with me. And what are the most common questions ushers get? I heard these a lot:

Thank you Kauffman Stadium. It was a great ride. Next time I visit, it will be with a ticket. I can't wait.

10 Comments

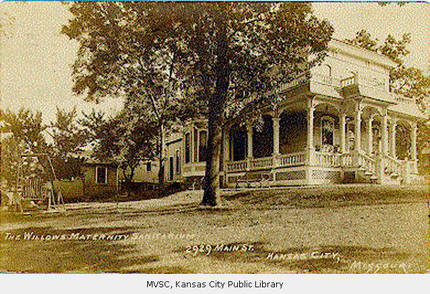

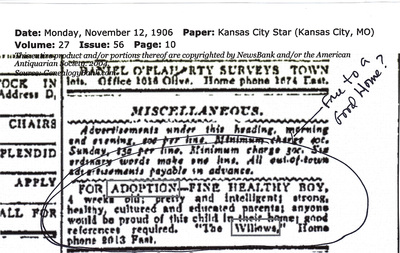

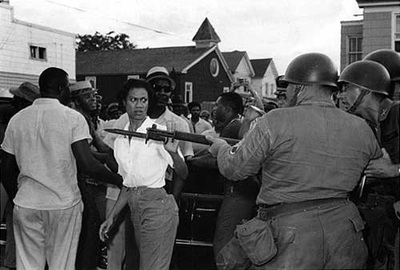

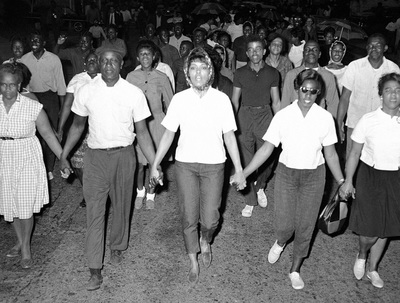

There's a lot in Harvest of Thorns that's near to my heart, but that portion of Earl Manning's life that takes place at the Howland Maternity Sanitarium might be closest. Today we don't know much about places like Howland; I certainly didn't. While talking to people a generation older, however, I learned of a time when a female student might suddenly leave school without telling anyone. "Gone to stay with relatives," or "taking care of a sick aunt" were typical reasons. Months later, the young lady would return, offering little in the way of explanation. Then, I learned of a place called The Willows. It was in Kansas City, at 2929 Main Street. There's a Residence Inn there now, but I never pass the corner of 29th and Main that I don't think of The Willows. It was gone long before I arrived in Kansas City, but its ghost has touched my life completely. My wife Robin was born there. Her story still grips me. A young woman, a girl really, became pregnant in the early 1960's. She was given train fare to Kansas City and took up residence at The Willows. It was a different time, a time anyone under forty will struggle to understand. Girls who became pregnant couldn't continue attending school in many areas. Places like The Willows thrived. The arrangement was simple. Young ladies came to The Willows to wait out their pregnancy. When their babies were born, they were put up for adoption. The new mothers were sent home, with little more than a passing glimpse of the life they'd carried. Its almost incomprehensible to think that The Willows and similar facilities actually advertised, but here are a couple ads. The first from the Kansas City Star in 1906, the second an undated ad likely placed in an eastern city newspaper. Click on them to enlarge. Since getting the itch to write, I've felt the need to pen an homage to The Willows. I hoped to base an entire book around it, and still might. Howland Maternity Sanitarium's appearance in Harvest of Thorns came after hours of research. I wanted to make sure I got it right. When you read about the long walkway leading to the street, the catcalls from passersby, and the manner in which rooms were assigned based upon wealth, know that I made the Howland Maternity Sanitarium as close to real as I could. And the kindness and gentleness of the staff, especially Earl Manning? I created them as I hoped the staff was at The Willows. After all, who doesn't want to believe that the first breaths of the person he loves more than anything were taken in a nurturing environment? For more about The Willows, including pictures and first-person accounts, look here. Birmingham? Selma? Nope. Cambridge Maryland in 1963-64. Last week I shared some personal remembrances from the 1969 integration of schools in Dorchester County, Maryland. Based on the responses I received, others had similar experiences. But there is more to the story than the recollections of a ten-year-old boy. Much more. Several years ago, I ran across a document prepared by the United States Commission of Civil Rights in 1977. This document, which you can read here, shares the not-so-pretty things that went on behind the scenes. Cambridge, the county seat, experienced a long and unflattering period of racial strife. A decade ago, NPR featured Cambridge in one of its reports. Many locals remember the visit by H. Rap Brown, a civil rights leader at the time, whose challenge, "If Cambridge don't come around, Cambridge got to be burned down" led to the torching of a black elementary school. These actions brought national attention, and sadly reinforced the racial stereotypes of many whites. Lost in all this was the segregation experienced daily in Cambridge. In the same NPR story, resident Sylvia Windsor spoke of one of the main business districts in town: "One side of Race Street was for the whites and one side was for the blacks, and they never crossed over and we never did either," That segregation carried over to the schools and like many communities of the time, black schools were underserved. Resident Enez Stafford Grubb told NPR: "Whenever we received a textbook, it was a used textbook, and there was always a slip with the name of white students by the time we got it." Dorchester County's first effort to abide by Brown v. Board of Education was a "freedom of choice" plan that would allow students to attend the school of their choice, regardless of racial makeup. Not much changed. That year, 1963, just two black students enrolled in white schools. Pressure mounted, The State Department of Education and the NAACP cited Dorchester County for ineffective desegregation efforts. In March, 1966, the county school superintendent was directed by the state to "prepare immediately for complete desegregation" by the 1967-68 school year. Very little happened. Black high school students continued to be bussed past white high schools. When pressed by the state, the superintendent stated the the district would go to court before meeting desegregation mandates. He defended the freedom-of-choice plan despite lackluster results. In 1967 a biracial steering committee was formed to study remedies, but the superintendent disregarded the recommendations. Two-thirds of Dorchester County's black students continued to attend segregated schools, and many were bussed excessive distances to maintain the status quo. It took the threatened loss of federal funds to finally get things moving. A deadline was set for September, 1969, the year my classmates and I started attending integrated schools. If only the story ended there. Sadly, continuing into the 1970's there was evidence of discriminatory treatment of black students and educators in Dorchester County. In 1971, the federal government gave the district 90 days to remedy inequitable employment practices. The superintendent's response: "There isn't any teacher, child, parent, or otherwise who feels discriminated against . . . I reiterate there isn't any way within 60 days we can tell you who is going to be in what school." The school board had had enough. The superintendent's resignation was accepted in June, 1971. Within a month, the new superintendent met all federal mandates. Three weeks later, he submitted a plan for total integration of county schools. What had dragged out for years, was completed in a few weeks. None of this was known by the sixth graders entering their second year at integrated Hurlock Elementary School. I can't count the number of times I've gone back and reviewed the report I've shared with you. It had that kind of impact on me. More to the point, it carried over to my writing. In Harvest of Thorns, you'll read of images and attitudes similar to those in Dorchester County a half-century ago. You'll read stories of hope and triumph, too; also like Dorchester County. Comments and similar experiences are welcome. I particularly welcome those from my classmates who may have experienced the other side of segregation in Dorchester County schools all those years ago. Leave your comments below or on my Facebook page. Thanks for reading!  It was 1969 when Dorchester County got around to integrating its schools. Entering fifth grade, I was unaware of the history being made or the struggles involved. The small community where I attended school previously had two elementary buildings; one for black children and one for white. That September, students in kindergarten through third grade attended the formerly black school, while Grades 4-6 went to the school I'd attended all along. That school, long gone, is pictured below. It seemed like a minor thing. That's how oblivious I was. Recently, I ran across something on the internet that made me realize how un-minor it was. I'll save that for my next post. But first, a history refresher: The Supreme Court ruled in 1954's Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka that separate but equal schools were no longer acceptable. States and local school districts were mandated to eliminate segregated schools "with all deliberate speed." Note that date - 1954. Note that mandate - with all deliberate speed. Anyway, in 1969, Hurlock schools integrated. What I remember most were the differences. Scores of black boys and girls where there had only been two or three; a climb in enrollment, that resulted in my fifth grade class being placed in the school gymnasium; names like Odise and Cordell appearing next to Bobby and Lisa on the class roster. Oh yes, and the black teachers. My fifth grade teacher was Mr. B.D. Lake. Not only was he the first black educator I'd encountered, he was the first male. Mr. Lake wore light-blue dress shirts, white shoes, and socks as colorful as the rainbow. He figured out pretty quick that the Wootten boy couldn't see very well, so he moved my desk right up next to his. That's where it stayed. I don't know if Mr. Lake was a good teacher, at least in terms of what we learned or didn't learn. Some classmates liked him, others didn't. I loved Mr. Lake. At Christmas, I convinced my mom to take me shopping for some colorful socks that I gave him at our classroom Christmas party. And what a party it was! Mr. Lake shut those gym doors, fired up the phonograph, and allowed us to dance to our favorite Christmas records. I brought a single by Alvin and the Chipmunks. Walter, one of my new classmates, brought "Funky Little Drummer Boy," by Sharon Jones and the Dap Kings, fueling my lifelong love for funk and soul music. Before the school year was over, I had my own pair of white dress shoes. I also remember Mr. Lake telling me that I was his favorite. Now I know that he probably told every child the same thing, but at the time. . . I would have run through a wall for Mr. Lake. So you can imagine, with fond recollections like these, how dismayed I was to run across a report detailing the actions leading to the integration of Dorchester County Schools in the 1960's. It's the kind of stuff you thought only happened in the deep south during the turbulent 1950's. It involves adults turning their backs rather than doing what's best for kids. It also, among other important times in the history of civil rights, inspired me to write Harvest of Thorns. I'll save that for another day. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed